Monkeypox has recently captured global attention as cases emerge in various parts of the world. This viral disease, while not entirely new, has sparked concerns due to its potential for human-to-human transmission and the unfamiliarity many have with its characteristics. Understanding the nature of monkeypox, its symptoms, how it spreads, and the measures we can take to protect ourselves is crucial in navigating this public health challenge.

The monkeypox virus belongs to the Orthopoxvirus genus, which also includes the now-eradicated smallpox virus. Despite this relation, monkeypox is generally considered less severe than smallpox, though it can still cause significant discomfort and, in some cases, serious complications. The virus was first identified in 1958 when outbreaks occurred in colonies of monkeys kept for research, hence the name. However, the natural reservoir of the virus is believed to be rodents and other small mammals, not monkeys.

Human cases of monkeypox were first documented in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Since then, the virus has primarily been reported in Central and West African countries. The current global outbreak marks a significant shift in the virus's behavior, with sustained transmission occurring in many non-endemic countries. This development has prompted health organizations worldwide to enhance surveillance and response efforts.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation

The incubation period for monkeypox typically ranges from 5 to 21 days, meaning symptoms can appear anywhere from less than a week to three weeks after exposure. The initial symptoms often resemble those of many other viral illnesses, which can make early diagnosis challenging. Patients commonly experience fever, often accompanied by chills and intense headaches. Many report profound exhaustion and muscle aches that can be severe enough to limit daily activities. Swollen lymph nodes represent a distinctive feature of monkeypox that helps differentiate it from other similar diseases like chickenpox.

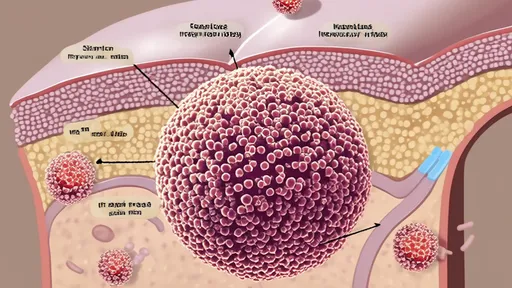

Within one to three days after the fever begins, the characteristic rash typically develops. The rash often starts on the face before spreading to other parts of the body, including the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. The lesions progress through several stages – beginning as macules (flat lesions), progressing to papules (raised lesions), then vesicles (fluid-filled blisters), pustules (pus-filled lesions), and finally crusts that dry up and fall off. The number of lesions can vary significantly from just a few to several thousand. The entire illness typically lasts two to four weeks, with the crusting stage indicating the end of the infectious period.

The clinical presentation of monkeypox appears to be evolving in the current outbreak. Many recent cases have shown atypical features, including lesions limited to the genital or perianal area, or appearing before the systemic symptoms like fever. Some patients have developed proctitis (inflammation of the rectal lining), while others have experienced severe sore throat that makes swallowing difficult. These variations in presentation highlight the importance of healthcare providers maintaining a high index of suspicion, even when symptoms don't follow the classic pattern described in textbooks.

Modes of Transmission

Understanding how monkeypox spreads is essential for controlling its transmission. The virus can be transmitted through several routes, with close personal contact being the primary driver of human-to-human spread. Direct contact with the infectious rash, scabs, or body fluids represents a significant transmission risk. This includes skin-to-skin contact during intimate activities, which has been identified as a major factor in the current outbreak. The virus can also spread through respiratory secretions during prolonged face-to-face contact, though this appears to require more sustained interaction compared to diseases like COVID-19.

Indirect transmission represents another important route of spread. The virus can survive on contaminated objects and surfaces, creating potential for infection when people touch these items and then touch their eyes, nose, or mouth. Bedding, towels, and clothing that have been in contact with infectious rashes or body fluids can harbor the virus. Personal items such as sex toys might also facilitate transmission if shared between partners. The potential for environmental contamination underscores the importance of thorough cleaning and disinfection practices in both household and healthcare settings.

Vertical transmission from mother to fetus through the placenta has been documented, highlighting the particular vulnerability of pregnant individuals. Additionally, transmission can occur through contact with infected animals, either through bites or scratches, or during activities like hunting, skinning, or preparing bush meat. While not common in the current outbreak, this zoonotic transmission route remains relevant in regions where the virus circulates in animal populations.

Risk Factors and Vulnerable Populations

Certain groups face higher risks of either acquiring monkeypox or developing severe disease. Individuals with multiple sexual partners, particularly men who have sex with men, have been disproportionately affected in the current outbreak, though it's crucial to emphasize that the virus can infect anyone regardless of sexual orientation. Close contacts of confirmed cases, including household members and healthcare workers without proper personal protective equipment, also face elevated transmission risk.

Those with weakened immune systems, including people living with HIV who are not receiving treatment or have low CD4 counts, may experience more severe disease. Similarly, children under eight years of age, pregnant women, and individuals with certain skin conditions like eczema appear to be at increased risk for complications. Understanding these risk factors helps target prevention efforts and ensures that vulnerable populations receive appropriate education and access to care.

Prevention Strategies

Preventing monkeypox transmission requires a multi-layered approach that combines personal protective measures with broader public health interventions. Avoiding close, skin-to-skin contact with people who have a rash that resembles monkeypox represents the most immediate protective action. This includes not touching the rash or scabs, and refraining from kissing, hugging, or having intimate contact with someone diagnosed with monkeypox. In situations where close contact is unavoidable, such as when caring for an infected person at home, both the patient and caregiver should wear well-fitting masks and the caregiver should use disposable gloves when handling lesions or potentially contaminated surfaces.

Regular hand hygiene remains a cornerstone of prevention. Washing hands with soap and water or using an alcohol-based hand sanitizer, especially after contact with someone who has monkeypox or with materials they have touched, significantly reduces transmission risk. Similarly, cleaning and disinfecting frequently touched surfaces and objects in homes and public spaces can eliminate the virus from the environment. In healthcare settings, implementing standard, contact, and droplet precautions is essential for protecting both healthcare workers and other patients.

For those at high risk of exposure, vaccination offers additional protection. Vaccines developed for smallpox have demonstrated effectiveness against monkeypox, and newer vaccines specifically targeting orthopoxviruses have been developed and authorized for monkeypox prevention. Post-exposure vaccination, ideally within four days of exposure, can prevent disease onset, while vaccination within 14 days might reduce symptom severity. Pre-exposure vaccination is recommended for laboratory workers handling orthopoxviruses and others at occupational risk.

Treatment and Management

Most cases of monkeypox resolve on their own without specific treatment. Management primarily focuses on relieving symptoms and preventing complications. This may include using medications to reduce fever and pain, maintaining adequate hydration, and caring for the skin lesions to prevent bacterial superinfection. Keeping lesions clean and covered can both promote healing and reduce the risk of spreading the virus to others or to different parts of the patient's own body.

For severe cases or individuals at high risk for severe disease, antiviral medications developed for smallpox may be beneficial. Tecovirimat has been authorized for treatment of monkeypox in several countries and works by inhibiting the virus's ability to spread within the body. In some circumstances, vaccinia immune globulin may be administered, particularly for patients with severely compromised immune systems. The decision to use these treatments should be made in consultation with infectious disease specialists and public health authorities.

Isolation remains an important component of case management. People with monkeypox should isolate at home or in a healthcare facility until all lesions have crusted over, the scabs have fallen off, and a fresh layer of intact skin has formed underneath. This typically takes two to four weeks. During isolation, patients should avoid contact with other people and pets, and not share items that could be contaminated.

Public Health Response and Global Coordination

The international response to monkeypox highlights the importance of global health security and cooperation. The World Health Organization has declared the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern, triggering coordinated action across countries. Surveillance systems have been enhanced to detect cases quickly, and laboratory testing capacity has been expanded in many regions. Public health agencies worldwide have developed guidance for healthcare providers, laboratories, and the public to ensure consistent approaches to prevention and control.

Equitable access to vaccines, treatments, and testing represents a critical challenge in the global response. Wealthier nations have secured the majority of available medical countermeasures, potentially leaving lower-income countries vulnerable. International organizations and donor countries are working to address these disparities, recognizing that uncontrolled transmission anywhere poses risks everywhere. Simultaneously, research efforts have accelerated to fill knowledge gaps about the virus's transmission dynamics, optimal treatment approaches, and long-term immunity.

Moving Forward with Knowledge and Compassion

As we continue to navigate the monkeypox outbreak, accurate information and compassionate response remain our most powerful tools. Stigma and discrimination against affected communities can drive cases underground and hinder control efforts. Public health messaging should emphasize that monkeypox can affect anyone and focus on behaviors rather than identities. Healthcare systems must ensure that testing, vaccination, and treatment are accessible to all who need them, without judgment or barriers.

While monkeypox presents new challenges, the fundamental principles of infectious disease control still apply: early detection, isolation of cases, tracing and monitoring of contacts, and protection of vulnerable populations. By combining these time-tested strategies with new scientific insights and medical advances, we can limit the impact of this outbreak. Continued vigilance, coupled with ongoing research to better understand this evolving public health threat, will help guide our response in the months ahead.

By /Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By Daniel Scott/Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/Oct 14, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Oct 14, 2025

By John Smith/Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By Megan Clark/Oct 14, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025