As the evening meal concludes and leftovers are packed away, a familiar question lingers in kitchens worldwide: how long can these refrigerated dishes truly last before crossing from economical to hazardous? The answer, it turns out, depends profoundly on what’s on the plate. A stark divide exists between the staying power of cooked meats and that of delicate leafy greens, a distinction rooted in basic food science and microbiology.

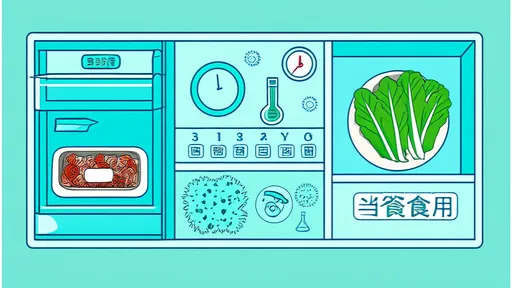

For many, the practice of storing leftovers is a routine act of thriftiness, a small rebellion against food waste. Yet, this common kitchen habit carries with it an undercurrent of risk, governed by invisible timelines of bacterial growth and chemical changes. The general guideline that emerges from food safety authorities is clear but often surprising in its specificity: cooked meat dishes can safely reside in the refrigerator for up to three days, while cooked leafy vegetables are best consumed immediately, within the same meal they were prepared.

The extended lease on life for cooked animal proteins—be it chicken, beef, pork, or fish—stems from their composition and how they interact with the cold environment of a fridge. When properly cooked, these meats undergo a transformation that eliminates most harmful pathogens. Refrigeration at or below 4°C (40°F) dramatically slows the growth of any surviving bacteria or new contaminants introduced during handling. This cold-induced lethargy among microbes buys the consumer a valuable window of approximately 72 hours. During this period, the rate of spoilage and production of harmful toxins remains low enough to be considered safe for most healthy individuals. The structure of the meat itself also plays a role; its dense protein matrix is less hospitable to rapid bacterial colonization compared to more porous food structures.

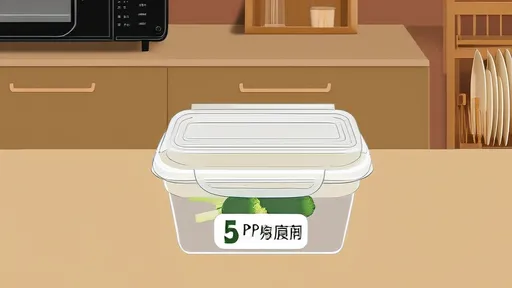

However, this three-day rule is not an absolute guarantee. It is a conservative estimate built on worst-case scenarios. The countdown begins the moment the food finishes cooking and starts to cool. Improper handling can truncate this safety period significantly. Leaving a pot of stew to cool on the stovetop for hours before refrigerating it, for instance, provides a dangerous incubator for bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus or Clostridium perfringens, which thrive in warm temperatures. Similarly, using unclean utensils to portion the food can re-introduce pathogens. The integrity of the storage container matters too; airtight seals prevent cross-contamination and moisture loss, which can accelerate spoilage. Even within the safe window, sensory checks are non-negotiable. Any off-putting odor, a slimy texture on the surface, or an unexplained sour taste are immediate red flags, demanding disposal regardless of the clock.

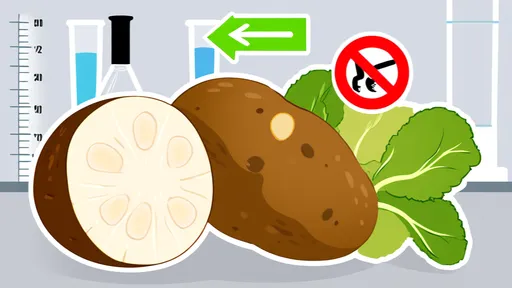

In stark contrast to the relative resilience of meats stands the dishearteningly short lifespan of cooked leafy greens. Spinach, kale, lettuce, bok choy, and other leafy vegetables present a perfect storm of factors that make them a high-risk leftover. Their high nitrate content is the primary culprit. While nitrates themselves are not inherently dangerous, certain bacteria that can survive cooking or be introduced post-cooking possess enzymes that convert these nitrates into nitrites. Upon reheating or even simply sitting in the fridge, these nitrites can further react to form compounds called nitrosamines, many of which are known carcinogens. The risk of this conversion increases with time, making prolonged storage a dangerous game.

Beyond the nitrate issue, the physical structure of greens works against them. Their large, thin, porous surface area offers a massive landing pad for airborne microbes and is difficult to clean thoroughly in the first place. Cooking breaks down their cell walls, releasing moisture and nutrients—creating a nutrient-rich, moist broth that is an ideal breeding ground for any bacteria present. Unlike the dense structure of meat, this soupy environment allows bacteria to multiply rapidly. Refrigeration slows this process but cannot stop it altogether. The result is that harmful bacteria levels can reach dangerous thresholds much faster than in meat-based dishes, often within hours of being stored. This is why the strongest advice from food safety experts is to cook only the amount of leafy greens you intend to eat in one sitting. The potential health risks simply outweigh the benefits of avoiding food waste.

The difference in spoilage rates between these two food groups necessitates a strategic approach to meal planning and leftovers. A savvy cook will design meals with these timelines in mind. A large roasted chicken or a hearty beef chili can be intentionally prepared in bulk, providing convenient ready-to-eat meals for the next two days. A wilting spinach salad or a stir-fry with bok choy, however, should be metered out precisely to avoid any remainder. This isn't just about safety; it's about quality. Reheated greens almost universally suffer a tragic fate, transforming from vibrant and slightly crisp to a mushy, unappetizing, and often discolored shadow of their former selves. The culinary loss is as certain as the safety concern.

Understanding the "why" behind these guidelines empowers home chefs to make smarter decisions. It moves food storage from an arbitrary rule to a logical practice. The three-day boundary for meats is a buffer against the slow but steady growth of psychrotrophic bacteria—strains that, unlike their heat-loving cousins, actually prefer cooler temperatures and can slowly multiply even in the fridge. For greens, the imperative to eat them immediately is a race against enzymatic activity and bacterial conversion processes that begin almost the moment the heat is turned off.

Ultimately, navigating the world of leftovers is an exercise in calculated risk management. The robust nature of cooked meats grants us a flexibility that supports modern, busy lifestyles. The delicate and chemically complex nature of cooked leafy greens demands respect and immediate consumption. By honoring this biological dichotomy, we can successfully reduce food waste without inviting unnecessary health hazards into our kitchens. The mantra is simple, yet powerful: plan your proteins for the week, but keep your greens for the moment.

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025